Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath officially removed Houston ISD’s elected school board and superintendent from power Thursday, replacing them with an appointed governance team and a new district leader, former Dallas Independent School District chief Mike Miles.

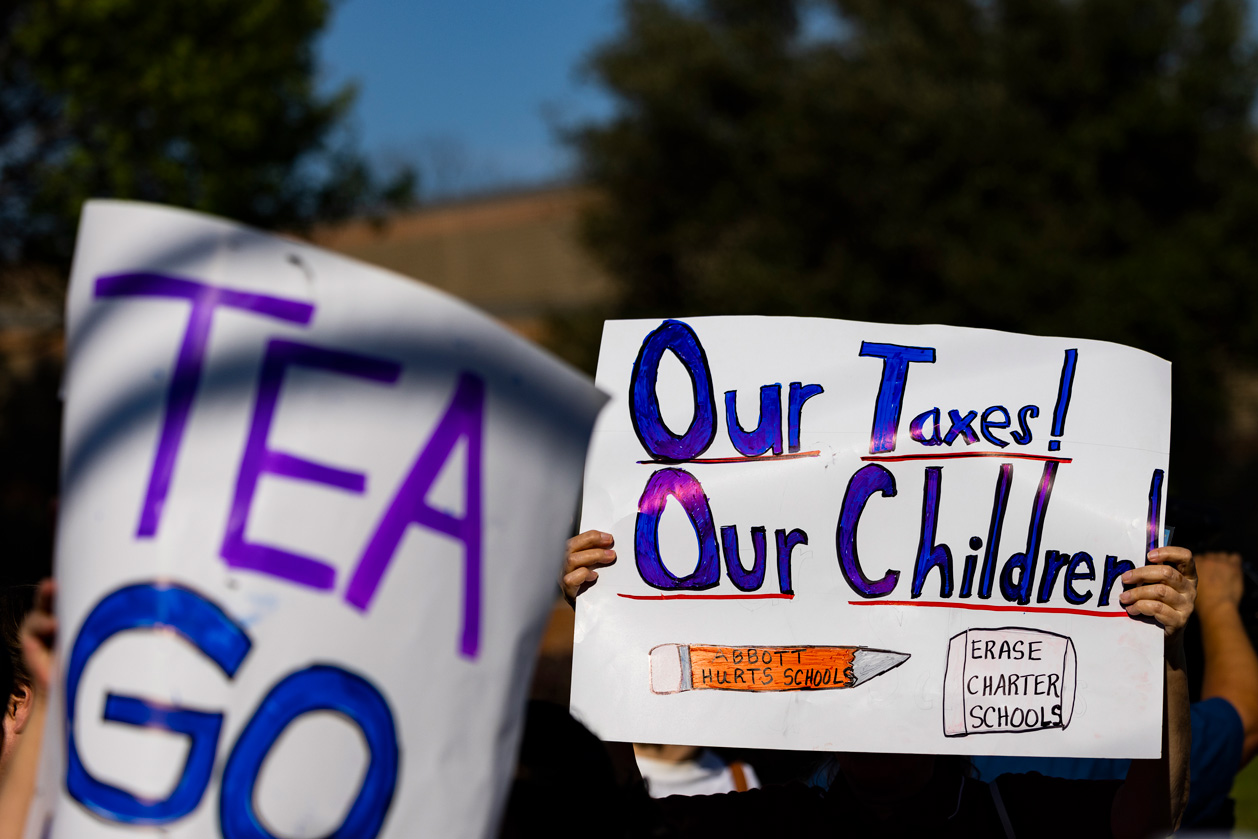

The long-expected choice of new leaders ushers in an era of dramatic change in Texas’ largest district, which failed to stave off punishing state sanctions largely tied to chronically poor academic results at one campus. Morath has said the leadership overhaul is necessary to address the district’s neglect of its neediest students, while many Houston-area political leaders and educators have blasted the takeover as an undemocratic, unnecessary power grab by Republicans in Austin.

By selecting Miles, Morath has entrusted HISD to a longtime collaborator known for pushing substantial changes in public school districts – and aggravating some educators in the process. Morath served as a Dallas school board member during Miles’ tenure, and they share a similar outlook on education policy.

The nine appointed board members include several parents of HISD students, as well as multiple members of the city’s business and nonprofit communities. One appointee is a former teacher and school administrator, while another works as a top official for the College Board, a nonprofit best known for developing the SAT exam and other tests.

“We were looking for people from a wide array of backgrounds, experiences and perspectives who believe all children can learn and achieve at high levels when properly supported and who can work together,” Morath said in a statement.

In an interview with the Houston Landing, Miles pledged to enact numerous reforms that will impact administrators and teachers across the district, as well as students attending historically low-rated campuses.

“This is an intervention, and there has to be some changes,” Miles said. “And with that comes some concern that the status quo will be shifted, and that concern will be real.”

But Miles’ appointment portends clashes with many of Houston’s political and education leaders, who oppose the Army veteran’s assertive leadership style and data-centric approach to teaching.

“My biggest concern is that he’s a person that’s pretty hard-driven, perhaps inflexible, and I’m not sure if he’s going to be able to build relationships with the community (and) the stakeholders, mostly Democrats here in Houston ISD,” said Sergio Lira, president of the Greater Houston LULAC Council and a former HISD board member.

Critics of the state intervention have also argued that HISD does not need overhauling, given that the district has a B rating under Texas’ academic accountability system and outscores many of the state’s large, urban school districts.

Nevertheless, Miles described HISD as a “tale of two districts,” with too many students receiving an inadequate education.

Miles said he plans to trim HISD’s “bloated and bureaucratic” central administration, study the potential need for school closures, revamp the district’s principal and teacher evaluation systems and divert more resources to high-need schools, among other tasks. Some reforms will begin immediately, while others will be shaped by conversations with community leaders and further research into the state of HISD, Miles said.

“At the end of the day, the adults have all the time in the world. Our kids have no time,” said Miles, who led Dallas from 2012 to 2015 and spent the past several years as CEO of a charter school network based in Colorado.

“This is not a traditional superintendent coming in, where (you’re) listening for three or four months, and then wait another six months to release a strategic plan. That always struck me as not the best way of going about business.”

While Miles forecasted significant changes throughout large swaths of the district, he said his administration is “not going to upset the applecart at all of the schools,” allowing higher-rated campuses to “do what they’ve always done.”

Miles will still need approval from the district’s new, nine-member board to enact some of his proposed changes, though Morath is expected to select board members who will support Miles’ plans. The nine appointees are Cassandra Auzenne Bandy; Ric Campo; Michelle Cruz Arnold; Janette Garza Lindner; Angela Lemond Flowers; Rolando Martinez; Paula Mendoza; Audrey Momanaee; and Adam Rivon.

In the interview, Miles outlined several key initiatives he hopes to prioritize and addressed some of the most contentious issues hanging over HISD.

Low-performing schools

Morath has tasked HISD’s new leadership team with raising achievement in the district’s struggling campuses, telling the Landing in March that “we don’t want to see any more multiyear D or F campuses in Houston.”

Miles said he plans to focus on placing and recruiting more-effective teachers in long-struggling campuses, improving the training delivered to educators working in those schools and ensuring that campus administrators are better-equipped to coach teachers. He added that the district will look to push more resources to those schools, without taking money away from other campuses.

“For a subset of schools that are not doing well, their classrooms are going to be looking way more engaging, the quality of instruction is going to be higher,” Miles said. “Kids gotta get the curriculum they need, and they’re going to get the supports they need as they move along.”

HISD administrators have employed some of the strategies referenced by Miles, including additional training and incentives for teachers to work in low-rated campuses.

HISD had 10 schools that would have received D or F ratings in 2022 under the state’s academic accountability system, but those campuses were not rated due to the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s down from 50 schools with those low ratings in 2019, the last pre-pandemic year.

School closures

Few topics stoke passion in HISD more than shuttering schools – and Miles isn’t shying away from the issue.

Miles said he will not recommend closing any campuses before classes resume in August, but he will spend the next year evaluating whether some schools should be mothballed in the summer of 2024 and beyond.

“There’s already been a study, but we’re going to do even more homework on that, and we most likely will bring to the board the following year schools that need to be closed to provide a better education for the student and for us to be more fiscally sound,” Miles said.

The Texas Legislative Budget Board and HISD’s past two superintendents have both suggested that HISD should consider closing some under-enrolled campuses. HISD currently operates dozens of schools with below-average enrollment, an issue exacerbated by the loss of roughly 26,200 students, or 12 percent of its total population, since 2016-17.

By closing schools, HISD could save tens of millions of dollars. The district also could move students to larger campuses with more classroom and extracurricular opportunities.

However, campus closures are a major disruption to families. In addition, some community leaders argue the district leaders too often shutter schools in predominantly Black, Latino and lower-income neighborhoods.

“There is a lot of concern about closing our neighborhood schools and chartering out neighborhood schools,” said Bradley Wray, a teacher at Deady Middle School who serves on HISD’s District Advisory Committee. “I just hope that doesn’t become the case.”

Central office and principal staffing

Miles reserved some of his harshest criticisms of HISD for the district’s central administration, which is primarily responsible for helping campus-level staffers carry out districtwide plans. HISD’s highest-paid employees generally work in central administration, which accounts for about 6 percent of the district’s budget.

“We have a central office that is bloated and bureaucratic, and we need to trim that,” Miles said. “And so, there’ll be some savings from central office. This is nothing new to HISD. The question is, how well do you implement that?”

Miles did not detail plans for cutting specific positions or departments, but he said the district has “too many people coaching people” and an excess of contractors.

At the campus level, Miles said he does not foresee removing principals from their positions based on past performance headed into the next school year. However, he said principals will be evaluated closely in 2023-24.

Shannon Verrett, executive director of the Houston Association of School Administrators, said HISD’s next leaders “must create a flow of communication” that brings campus and district chiefs into the fold.

“I think one of the biggest fears is that parents and teachers and administrators are going to be left out of the decision-making,” said Verrett, a retired HISD assistant superintendent. “And if that’s the case, it’s going to be an uphill battle for us to really improve outcomes for all students.”

Principal and teacher evaluations

One of Miles’ signature projects in Dallas involved overhauling the district’s educator evaluation system – and he expects to replicate those efforts in Houston.

First, Miles said he wants to put a pause on HISD’s Teacher Incentive Allotment plans, which were on track to take effect in 2023-24. The Teacher Incentive Allotment is a Texas program that primarily boosts the salaries of highly rated educators in districts employing a state-approved teacher evaluation system.

Miles said he believes HISD’s evaluation model is “not rigorous and not tied to the quality of instruction.” In addition, he said he wants to roll out a principal evaluation framework first.

“(It’s) totally unfair to a teacher if a principal doesn’t know what they’re doing,” Miles said. “We’re going to train principals first, and teacher evaluation will come second.”

Some Dallas educators embraced Miles’ evaluation models, particularly given that they tied pay to performance. Teacher ratings were based on administrators’ observations, students’ improvement on various tests and surveys taken by students.

However, other teachers argued that the system didn’t accurately capture teacher effectiveness and bred distrust between co-workers.

Charter schools

Miles’ leadership of Third Future Schools, a charter network based in Colorado, has prompted questions about whether he will get cozy with outside operators.

The district’s elected board members have generally opposed charter school expansion in the Houston area, primarily arguing that charters drain financial resources from traditional public schools and are less likely to enroll students with more academic and behavioral needs.

Miles said he hasn’t been in contact with charter school networks about operating HISD campuses, and he doesn’t plan to bring any charter operators into the fold early in his tenure. He did leave open the possibility of working with charter networks in the future – though he doesn’t envision Third Future Schools as a potential partner.

“My first job, my first priority work area is to make sure that all of our kids get a really good education and really good school,” Miles said. “So I’m going to work on that, making sure our schools are improved systemically, and then we’ll see if we need any charter operators in the district.”

Special education services

Another task Morath assigned to HISD’s new leadership involves improving the delivery of special education services.

In recent years, multiple investigations and audits have documented widespread issues with HISD’s support for students with disabilities. HISD currently has two state-appointed conservators in the district to address its special education shortcomings.

Miles said he wants to ensure special education teachers get better support from principals and more time to focus on instruction. He also noted that about 20 percent of principals’ ratings under his proposed evaluation model will be tied to special education compliance and student achievement.

“This is not just the HSD problem,” Miles said. “This is a problem in a profession, where students with special needs are often getting a less than rigorous education curriculum, they are not being taught to read at the level that all kids should be able to read, they’re not given the proper instruction or supports to be able to be successful after high school.”

Miles acknowledged that his Dallas administration “didn’t do as good of a job (as) we needed to” in delivering special education services during his tenure. More than 2,000 Dallas students referred for special education supports didn’t receive help between 2017 and 2021, according to an internal investigation by the district. The inquiry didn’t cover Miles’ time in leadership, which ended in 2015, but he said he deserves some blame for the years-long issues.

This story was produced by the Houston Landing, a nonprofit news organization that covers the Houston region. Learn more and subscribe to the Houston Landing’s newsletter at https://houstonlanding.org.